The right ash, the right heat,

the right position of wind, dune and saltbush:

a technology of Fire. The knowledge.—from Billy Marshall-Stoneking, “The Seasons of Fire.”

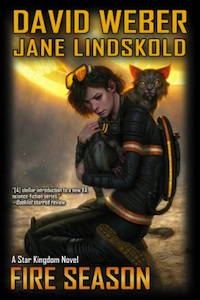

Jane Lindskold and David Weber’s first novel-length Honorverse collaboration, Fire Season, is a direct sequel to Weber’s arguably-unsuccessful solo attempt at writing for young adults. I reviewed A Beautiful Friendship last year, without an excess of love. I’m happy to acknowledge that Fire Season is much more successful, both as a novel and as a standalone work, than its predecessor. But it still doesn’t have the right ash, the right heat to burn brightly in the Young Adult firmament.

Especially when it can’t quite make up its mind whether it wants to be a middle grade novel, a YA, a Heinleinesque juvenile, or an adult prequel to the Honor Harrington books.

Fourteen-year-old Stephanie Harrington, fresh from the events of A Beautiful Friendship, has settled down as a probationary ranger in the Sphinxian Forestry Service with her treecat friend, Lionheart – who thinks of himself as Climbs Quickly. The inability of treecats (telempathic amongst themselves) to communicate with humans on anything other than a crude level is one of the novel’s driving tensions. As are Stephanie’s first steps into adolescent social competence.

But for a novel aimed at YA or even slightly younger readers—a genre dominated by tales of government conspiracies and dark secrets, friendships strained or broken and angst-ridden love—the conflicts here have a noticeable lack of drama and emotional intensity. This lack doesn’t seem to gel well with its intended audience: thirteen and fourteen year olds in the past may have no choice but to read novels in the style of Heinlein juveniles, if they were interested in science fiction/fantasy, but the explosion of the YA market has been showing us what YA readers think worth notice for quite some time now, and the vast majority of titles employ a much more immediate style.

(And for a novel that spends some of its time moralising on how teenagers don’t like to be talked down to, it really doesn’t demonstrate the greatest of confidence in the intellect and understanding of its readers. It’s very heavy-handed about the messages it wants its audience to receive – and it’s far from obvious they’re all good messages.)

That takes care of the preliminary kvetching. It’s fire season on Sphinx, at the tail end of the planet’s Earth-year-long summer. Stephanie’s life is complicated by her ranger duties when forest fires crop up, and by the visit of an off-world anthropological team, come to Sphinx to assess the sentiency of the native treecat population. Anders, the son of the team leader, comes with them. He’s only a year older than Stephanie herself, and predictably, the two hit it off. But when the anthropological team ignores instructions and gets themselves stranded in the middle of the wilderness, and when a massive forest fire breaks out that threatens not only human settlements but a whole clan of treecats, both Stephanie and Anders find themselves forced to work harder than they’ve ever done before.

Readers of Lindskold’s Wolf series will recall that she has a good touch with action scenes, and Weber is renowned equally for his techsposition and his battle scenes. The action sections of Fire Season, particularly the ones from the treecat perspective, achieve an urgency and personality that the rest of the novel, with its distant, somewhat analytical tone, never quite reaches. The emotional connection—the angst, the drama—so beloved of YA readers just isn’t there.

And ye gods and little fishes, guys, I hate to say it? But some of the descriptive writing here is really quite a) out of character for teenagers, and b) noticeably sexist.

Kate Elliott recently wrote an excellent article, “The Omniscient Breasts: The Male Gaze Through Female Eyes.” So much of how Stephanie relates to her own body, and to the bodies of her female peers, is mediated through such a clearly objectifying lens (and one which appears to equate, at least on a subconscious level, teenage sexuality with moral hazard) that it’s hard not to see an adult male gaze at work.

We were teenage girls once, and it’s not so long ago that we can’t remember—quite clearly—how it felt. (And I got enough female socialisation in all-girls-school that I’ve some idea how a wide variety of girls bemoan their bodies – LB.) (Likewise, in an all-women college – JK.) Very little of Stephanie’s thoughts about breasts, and body types, and her peers’ bodies, feels authentic.

That’s before we come to the distant and assessing—and distinctly adult—gaze of our other teenage protagonist, Anders.

She immediately began to comb her much shorter white-blond hair into a style rather like a cockatoo’s crest. Her eyes proved to be ice-blue. The light hair and eyes made a marvelous contrast to the sandalwood hues of her complexion. Anders spent an enjoyable moment contemplating this delightful proof that female beauty could come in such contrasting packages. [Fire Season, p86]

Here we have a dispassionate, adult reifying voice, rather than something that seems like the authentic reaction of a teenager. This is a style and tone that’s repeated in a manner which feels disturbing and alienating just a few short paragraphs later.

She’d thrown her shoulders back, raising her right hand to toy with the closure on her flight-suit, ostensibly because she was warm—out on the field, Anders could see that Toby and Chet had already divested themselves of their suits—but in actuality to draw attention to what she clearly thought of as irresistible assets.

Those bouncing breasts were quite remarkable, especially on someone who was probably not much more than sixteen, but Anders thought the approach rather simplistic—and even sort of sad. What a pity she had to offer herself as if she was some sort of appetizer. [Fire Season, p88-89]

Leaving aside for one moment the narrative reinforcement of the objectifying gaze, does this sound remotely like the perspective of a boy who is himself about sixteen? You’d expect a sixteen-year-old to experience a more visceral reaction, something a little more internally complicated than SECONDARY SEXUAL CHARACTERISTICS DEPLOYED TOO OBVIOUSLY: SLUT WARNING SLUT WARNING. Ahem.

You’d expect something less detached and dispassionate. Less disappointedly adult in his concern for what’s framed as her “simplistic” sexual forwardness. Lay the charge of cranky humourless feminist all you like—yes, yes, it’s true, we’ve heard it all before—this is still not a good portrayal of adolescent sexuality. One might go so far as to call it downright unhealthy.

The fire-fighting, treecat-rescuing, stranded-humans-rescuing climax is a solid set of action scenes, during which it’s possible to forget the novel’s other flaws. But the dénouement is handled with off-hand speed, wrapping matters up in one of the novel’s shortest, and for its length, most infodump-heavy chapters.

It’s not a particularly satisfying conclusion – but then, all things considered, Fire Season is hardly a particularly satisfying book. Neither fish nor fowl nor good red meat, it’s caught in a disappointing limbo of cascading could-have-beens. It could have been decent space (or planetary) opera in Weber’s usual form – but it was trying too hard to appeal to a younger crowd. It could have been decent YA – but compared to Zoe’s Tale, or Unspoken, or Across the Universe,¹ it looks rather more like a failure of the mode.

A different approach could have capitalised on the persistent popularity of the Warriors series (ongoing since 2003) but it shows no awareness of existing traditions in animal and intelligent non-human stories² for a youthful audience. Readers raised on the intrigue and politics of the Clans may find the dryly delivered glimpses into treecat culture less than… well, satisfying.

Like A Beautiful Friendship, this is another one for Weber completists. But I wouldn’t expect your teenage friends and/or relatives to greet it with much enthusiasm.

¹Or even Academy 7, which hits many of my narrative kinks but for which I would never claim any excellence of form.

²In addition to a significant number of novels about animals for children, it’s common to find stories whose protagonists are intelligent non-humans or animals themselves: for example, Charlotte’s Web, The Mouse and the Motorcycle, or The Guardians of G’ahoole. Adolescents and younger readers not only have much against which to compare Fire Season, but also have a demonstrated tendency to anthropomorphise “animals” in a way that adults don’t. Consequently, the political question of treecat sentience will come across as more of an obvious test of faith, like being able to cross into Narnia or hear the Polar Express, rather than a realistic challenge.

Liz Bourke is a professionally humourless feminist as well as a cranky hard-to-please reviewer. Find her @hawkwing_lb on Twitter.

Jenny Kristine is a YA librarian by day and a mad scientist by night. She reads books for fun and profit.

I can’t say I’m all that surprised. I’ve stopped reading both of these authors because, despite their strengths, they fall down on the other 80% of the book. I have better uses for my time.

I sure would like some quality YA space opera, though.

Perhaps Weber should be classified as teaching situational ethics to young adults via science fiction. So yes the novels are probably never going to be among top 20 best sellers for YA. But that does not mean there is not a YA market for the less frivolously minded. Might possibly be Top 40…even if anything less than Top 10 is failure in the reviewers mind.

The reviewer has an awefully narrow definition of the target audience demographics. The reviewer definitely talks down when assuming all YA novels “must be all action and angst without any pause for thought — simple and not complex”…i.e. almost totally frivolous. I am not saying that you are not correct for the most popular segment of YA. LOL. But then again if your criticsm is not being in the style of typical YA best sellers…well the SciFi genre itself is outranked by close cousins of urban fantasy, superhero/videogame novels, also old standards of mundane school teen romance (including sports backgrounded), and vacation-romance (often with pets providing meeting opportunity).

However, that said Weber novels are definitely not for everyone. He does have a pendantic tendency to spend too much time setting up a giant chessboard as framework for the infrequent action/direct conflict sequences. In fact Weber’s major weakness is that he tends to paint a scenario of inflexibly opposed sides. Even if the reasons for such positions are clearly given, its unlikely that such cohesive group dynamics occur in the real world.

P.S. The lessons of situational ethics are NOT always good (uplifting). I would certainly hope that YA readers are old enough to deal with that because the next category is legal adult.

However, assuming YA readers have not yet had experience of all ethical situations and all possible outcomes and little patience or inclination to figure it all out by themselves…perhaps some of Weber laying it all out is not bad assuming ethical behavior is desirable. Definitely different than popular urban Vampire novels which unhesitating march through action sequences emphasizing survive or die options with few shades of gray.

wunder:

Across the Universe is good, if you haven’t read it. But I would love more ya space opera too! and it would be nice to have some where the romance is not quite so prominent. (I like romance! but I also like variety)

WellDuh:

Do situational ethics involve deciding that, when people’s lives hang in the balance, the important thing is that your parents would think that your choice is the mature one? Or perhaps your argument is that situational ethics requires slut-shaming teen girls?

In either case, I will tell you what is completely lacking in Fire Season: ethical concerns that arise from science fiction scenarios, as opposed to ones lifted whole from modern life and merely placed among science fiction scenery. The one ethical concern that might fit what you are talking about: the sentience of Treecats and their overall treatment, is – as mentioned in the review – severely compromised by the authors’ lack of understanding of how the average middle school reader will approach this question, given how they have framed it.

What remains instead are questions about drugs, bullying, sex, sneaking driving lessons, and a whole list of issues that are better suited to a realistic fiction novel rather than a science fiction one. Most of which are treated with the same level of complexity and nuance as the training I got in DARE in 6th grade.

If you are looking for young adult and upper middle grade science fiction that is well written, popular, and presents complex ethical questions to readers (ones that make proper use of the science fiction setting), I suggest looking at The Giver, The Hunger Games, Across the Universe, Unwind, Little Brother, Uglies and Carrie Ryan’s zombie series. And that’s just to start.

“I’m happy to acknowledge that Fire Season is much more successful, both as a novel and as a standalone work, than its predecessor. But it still doesn’t have the right ash, the right heat to burn brightly in the Young Adult firmament.”

Huh? A Beautiful Friendship was a much better novel (YA and otherwise) than this weak sequel. I’m also a bit confused about how the reviewers immediately jump to the conclusion that Weber is the one to blame for any sexism present in the book. It’s a collaboration after all and Weber isn’t exactly well known for turning his female character into sex objects. In fact I didn’t recognice much of the writing in this book as Weber’s at all and I suspect Lindskold had a lot to do with the transformation of the intelligent, courageous heroine from book one into the stereotype teenager (brat) Stephanie is in Fire Season.